My research connects fundamental theory with phenomenology to understand how quantum systems evolve, interact, and organize under extreme conditions.

Heavy-Ion Collisions

When heavy ions collide at velocities close to the speed of light, as in the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), the violent event creates a fluid-like state of matter made out of subnuclear particles, quarks and gluons. This extreme state, the Quark-Gluon Plasma (QGP), holds the key to the fundamental properties of hot nuclear matter, which plays a key role in understanding the early universe and unlocking deep questions on the behaviour of matter at extreme conditions. However, due to the extreme complexity of these events, to extract these properties from the rich experimental data obtained at RHIC and the LHC accurately, one must rely on dynamical models capable of accurately describing the space-time evolution of such complex events.

My research in heavy-ion collisions focuses on the modelling of heavy-ion collisions, particularly understanding the first femtosecond of the collisions. While short, these epochs encode key information about the mechanisms that drive the approach to the thermally equilibrated QGP. For this I develop and study theoretical descriptions of the initial and pre-equilibrium dynamics, emphasizing how the geometry, fluctuations, and energy deposition at early times influence the subsequent evolution of the medium. In parallel, I also study how electromagnetic probes, such as photons and dileptons, can carry undistorted information about the quantum fluctuations of the initial state of a heavy-ion collisions, as well as the microscopic interactions of the medium before it fully thermalizes.

High-Energy QCD

At very high energies, the structure of hadrons and nuclei becomes dominated by gluons carrying a small fraction of the longitudinal momentum, the so-called small-x regime of Quantum Chromodynamics (QCD). As the nuclei approach each other before a high-energy collision, the acceleration provides energy for the quarks within the nucleons to radiate gluons, which radiate more gluons, resulting in a fast increase of their population. This trend is maintained until the non-linearities described by QCD take over and stop the fast increase. At this point, the nucleus becomes saturated, leading to the phenomenon of gluon saturation. Understanding this regime is crucial for describing the initial conditions of heavy-ion collisions and for testing QCD as a self-consistent theory of strong interactions.

My research in this area focuses on modeling and characterizing the high-energy structure of nuclei within the Color Glass Condensate (CGC) effective theory. I study how we can harness the dynamics of simpler systems, such as proton-proton and proton-nucleus, and the photonuclear collisions – in the upcoming Electron-Ion Collider (EIC)- to better understand the initial instants of Heavy-Ion Collisions. I have explored how fluctuations in the gluon fields shape the spatial and longitudinal structure of the colliding nuclei, and manifest in observables sensitive to saturation.

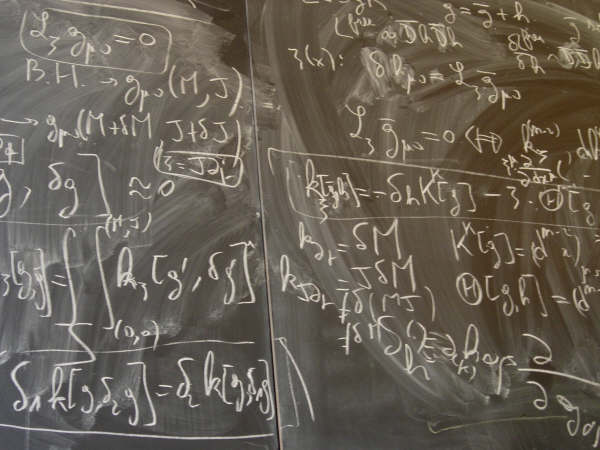

Quantum Field Theory

My research in quantum field theory mostly focuses on understanding how quantum systems evolve in real time, particularly when they are driven far from equilibrium. These situations challenge our traditional tools, as the usual approximations of thermal or perturbative physics often break down. I am interested in how macroscopic behavior — such as equilibration, transport, and collective motion — arises from the microscopic interactions of quantum fields.

To address these questions, I study field-theoretical frameworks that capture the dynamics of interacting systems beyond equilibrium and linear response. This includes exploring how correlations develop, how conserved quantities, such as energy, momentum and angular momentum are redistributed, and how approximate descriptions like hydrodynamics emerge from the underlying quantum dynamics.